Bobby Fischer and the Absence of Mercy

A portrait of genius built on precision, detachment, and the void of obsession.

➢ EDITOR’S NOTE: En Vogue et Veritas is the evolution of Critically Yours. Each piece will be free to read until September 30, 2025, when the series becomes exclusive to paid subscribers. Thank you for being here at the beginning. ☆

En Vogue et Veritas is a series exploring the figures I find most compelling by way of ethos, pathos, and logos, using style as a symbolic language for how we shape and disguise the self.

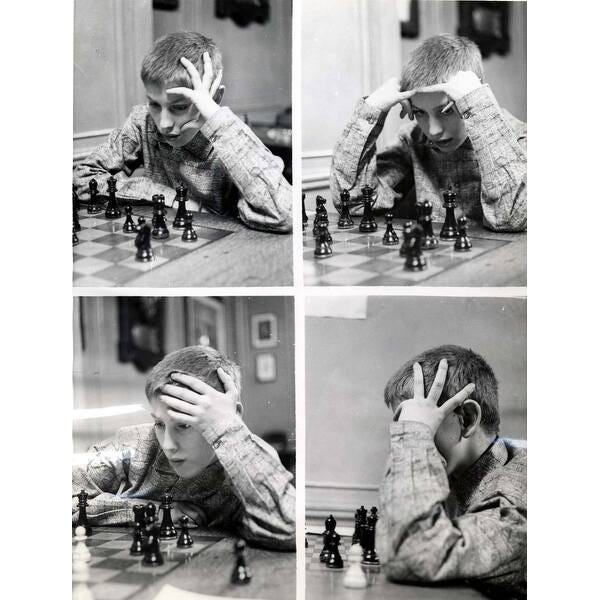

When I was young, I watched a movie about a man I’d never heard of before. His name was Bobby Fischer, and he was a prodigious chess player. He was young, maybe around my age, 13 or 14. He was not very nice, reveled in isolation, and was quite curt. He adored the game; you could see the potential and possible moves flitting through his mind. His eyes wavered between a soft focus and a deep stare. He loved chess in a strange way: it didn’t feel benevolent, it felt consuming, dominating. He reveled in it, screamed about it, was grotesquely obsessed with it. To play with Bobby was to incur a wrath others were forced to endure. I was completely fascinated by him, and though I can’t quite tell you why, I still am.

I feel as though if he were in the room with me, I could sit quietly and watch him play the game for hours. Me, only knowing the essentials of chess, and him being a grandmaster, I highly doubt my company would be encouraged. I don’t think he would even enjoy me there, in my silent marvel, but there is something about genius I find intoxicating. I don’t want to touch it, or feel its adoration, I am simply enraptured in its company.

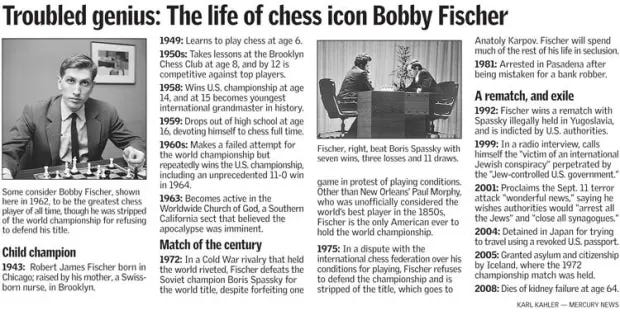

In this edition of En Vogue et Veritas, I analyze the man that was Bobby Fischer: one of the most brilliant, deeply flawed humans of our time. Born a brilliant prodigy, he was a symbol of hope for Americans during the Cold War. He died a paranoid, vitriolic man, ideologically vile, imprisoned by his own mind. His gift for chess was a joy to behold; to see such striking beauty emanate from the human mind is almost divine. I am disturbed by the idea of two violently different capabilities alive in the same man— so take this as I intend it: a study, not a celebration.

Through ethos, pathos, and logos, I shall attempt to dissect my fascination. However, I am painfully aware that to study Bobby Fischer is to chase meaning through absence.

Section I: Ethos, The Style of Character

Ethos /ˈē-ˌthäs/: From the Greek êthos, meaning character, custom, or moral nature.

Bobby Fischer was raised by a single mother in Brooklyn, New York, whose work and frequent activism left her child alone more often than not. During these hours, six-year-old Fischer taught himself how to play chess—a new realm that burned out all others. Chess became his sole focus and desire, the only thing that made absolute sense to him. For this, he forfeited all social contact. His obsessive relationship with the game continued to foster his genius, alongside his emotionally volatile behavior. It seems that his behaviors were dealt with in a passive, nontraditional manner—never encouraged to find a balance between the extreme temperaments he experienced. Instead, he was lionized for his singular brilliance, which made his outbursts perhaps tolerable; he created a psychological environment in which chess was both his sanctuary and his territory of war. He sought to dominate. He sought perfection. He abhorred ‘cheap wins’ and gave a god-like worship to the idea of the ‘perfect game.’ His ethos was completely rooted in monomania and dominance—he trusted no one, relished in demeaning his opponents, and treated his ability with a god-like reverence. He didn’t seek connection; he sought control.

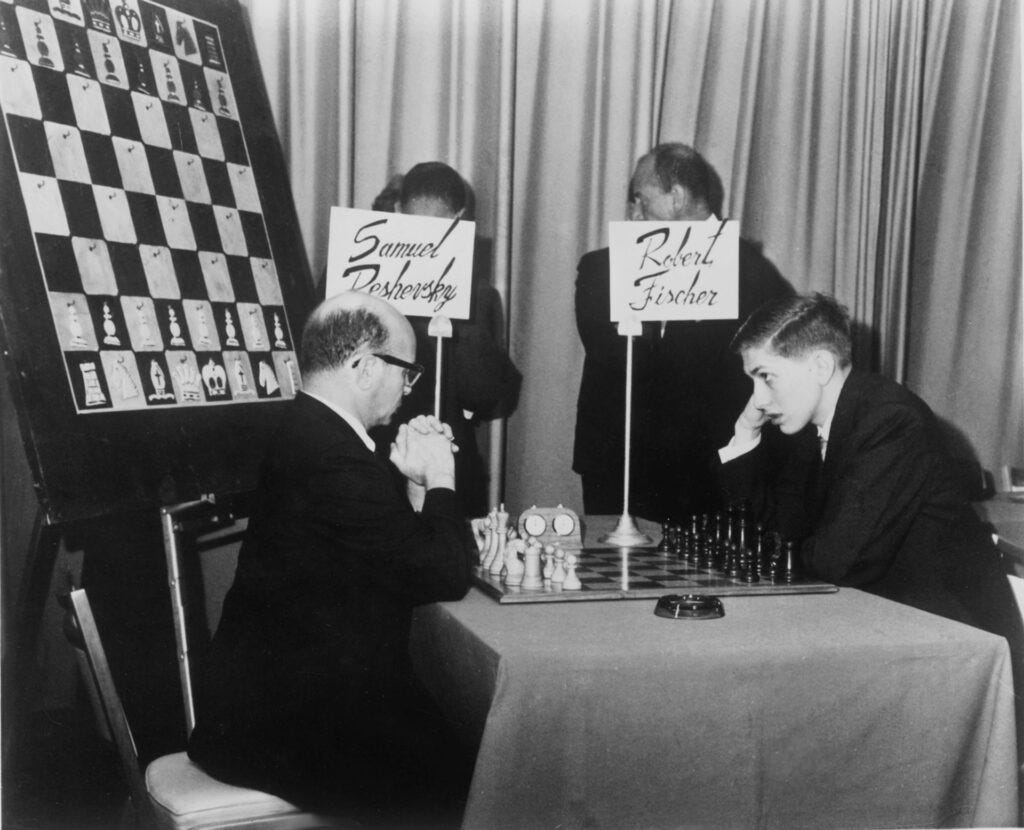

In this person, of all people, I would have expected this level of control to seep into his tailoring. Not through designer garments (as I cannot see him ever being so consumed in another’s creation), but at least a press of a collar. Wrong, I was! When he was young, he dressed like someone who didn’t care if he was on display. He wore garments that looked as though they’d just been rummaged from the bottom of the hamper. Fischer had no care for aesthetics—not even harboring anti-fashion so much as a complete lack of it. He dressed like a schoolboy who was a bit too serious for his age, and though he complained openly that his suits were ill-fitting, when offered a custom one, he refused. In the midst of his career, he had some tailoring and bespoke suits created, but they seemed to be more about his current state of mind than the clothes themselves. When he was young—and as he devolved into old age—he seemed to ebb back into a style that reflected both his disdain for the outside world and his singular focus on the game.

He seemed to spit in the face of all that was not created by himself, that did not fit in the chaotic box he built for his mind. There is no evidence whatsoever to suggest Bobby Fischer thought about fashion. However, it’s perhaps one of the things that makes the youngest-ever grandmaster so fascinating to me. The dichotomy of it all—I can’t quite explain. I’m sure he found it frivolous, beneath him to care about. However, if there was one thing he cared for, it was chess—and his relationship to it. I suppose chess never holds up a mirror to your body, only your mind.

Section II: Pathos, The Style of Emotion

Pathos /ˈpā-ˌthäs/ (noun) From the Greek páthos, meaning suffering, experience, or emotion, the emotional resonance of one’s feelings.

Some people, they wear their emotions like armor, layered and deliberate. Others, like Bobby, simply disappear into their obsessions until there is nothing left that separates them. They become a void, all-consuming.

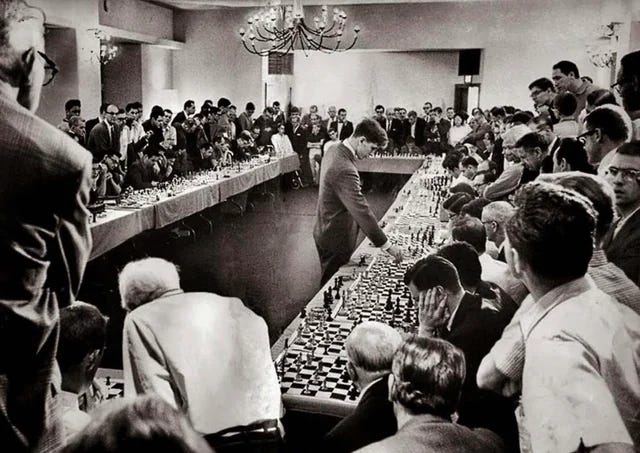

Bobby Fischer’s gameplay could be characterized by a relentless pursuit for domination. He reveled in showing off his intelligence, often leading his opponent into a fate they never saw coming. He was known for bold, dramatic moves that would emotionally torment his opponents, shocking with unexpected plays that made the tension he invoked a third player in a two player game. In his youth he played in several simuls, where one player walks from board to board playing against dozens of opponents at once. This was a literal display of myth come to life, the image of a lone boy, genius in his precision, surrounded by a sea of challengers, the audience silently craning their necks to catch a glimpse. His genius became ritualized, his lightening fast moves feeling like slow motion to his opponents. While Fischer paced around the crowded room he because more and more isolated in his superiority, turning chess from a game into his own brand of psychological warfare.

Fischer rarely spoke of feelings. But they bled through the edges of his rigidity—through his paranoia, his solitude, and, later, his breakdowns. Beneath the steely control was a man deeply marked by abandonment: his father absent, his home unstable, his social life nearly nonexistent. He was mocked, envied, feared. He never felt like he belonged anywhere, except across from an opponent.

There was a tension in his presentation: Fischer wanted to be taken seriously, but he had no interest in conforming to charm or fashion. He lacked the vanity and finesse the looks needed to bring it full effect; It was a very obvious contrarian statement, he did not care for any rules that existed outside of his own realm. He refused conform, to give in to a society he thought he was better than. I suppose I can conclude that his clothing, all of the mannerisms inside the way he dressed revealed that strategy was what he cloaked himself in. It eclipsed all empathy for his fellow man, even (and sometimes especially), in the realm of chess; his quest to reach mastery left no room for grace.

Section III: Logos — The Style of Thought

Logos /ˈlō-ˌgäs/ (noun) From the Greek lógos, meaning word, reason, or discourse. The logical structure behind an idea.

When I think back to my first introduction to Fischer, I remember the near-desperate wish I had to be able to be like him, to see like him. I imagined a man with a mind that could see far beyond the limits of my own imagination, someone that could see so much with no effort at all, it would make my limited understanding of the world a chore to understand.

I remember being captivated by his obsessed nature, his fanatical study of chess openings, every move backed by impenetrable reason, sought for and declared from hours of labor. His opening move, 1.e4, which he proclaimed was “best by test,” didn't sound like a mere preference to me, it was a declaration of his rational superiority. He prepared for his opponents with such depth of knowledge that he could narrow down what kind of game they would play within the first few moves. He didn’t practice with other members of the community, as was standard, he isolated himself. He believed that truth and victory could only be found alone. His genius was his only companion, a ghost in the realm of the living. It haunted him, demanded from him, ate him alive, and he lived to feed it. His avoidance of expression, through fashion or really anything, was never just distaste. I don’t know if, for all of his brilliance, he was ever able to see beyond the board, if he could give meaning to human existence. I don’t believe he was happy. I don’t even think he relished so much in his intelligence, I think he just was a man obsessed with a game. He suffocated everyone around him with his obsessive compulsive need to dominate, he wilted any flower that grew an inch outside the lines. He wanted the world to be like chess: rule-bound, formulaic, definitive.

Now, I understand things differently. The image I created in my mind was a mirage, the man was far worse. There is nothing romantic about his style of thought, because the logos of Bobby Fischer is a closed loop. What he called truth was only his will, not reason. It was not a living ideology, but the idea of one. His intelligence was all consuming, he had no other outlet, nothing outside of chess. His intellect didn’t bring him joy, only chess did. If Einstein reimagined the universe and Mozart heard symphonies in silence, Bobby Fischer saw all of life play out in 64 black and white squares.

After winning the World Championship in 1972, Fischer spiraled, hiding from the public eye, refusing to defend his title, eventually living in a self-imposed exile. He was erratic, disheveled, nearly terrifying. As he aged he became more and more psychologically distraught, his worldview left no room for collaboration, contradiction or ambiguity. He threw temper tantrums on a world-wide scale, descended into Nazi belief systems, and claimed to be thankful for the September 11th terrorist attack on United States. Bobby Fischer, the youngest grandmaster in the world, descended into madness.

Closing Reflection

I laugh out loud at the idea of Bobby Fischer ever reading this piece (albeit he is dead, so I have no worries), but I am certain he would find me increasingly dull and utterly lacking in complexity. To be intrigued by another person, I think, he would find quite rudimentary. Alas, I am no prodigy, and have simply been gifted with an endless capacity for curiosity, so it goes.

With great personal aesthetic,

Alexandra Diana, The A List