The Monarch of Madness

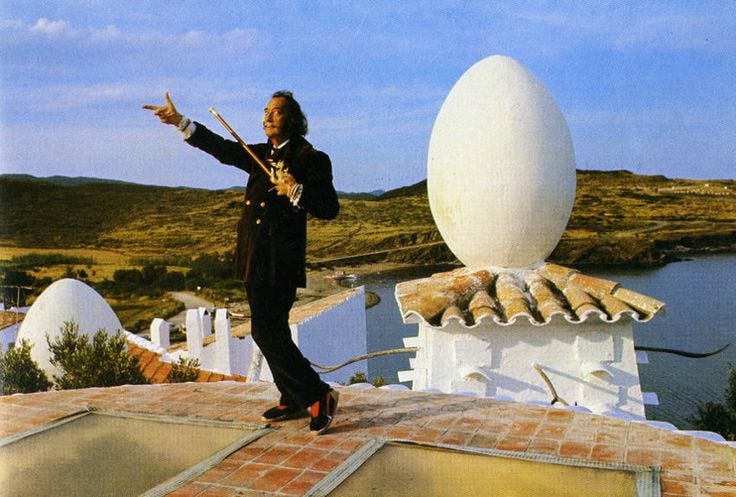

An exploration of the genius, grief, and grandeur stitched into the wardrobe of Salvador Dalí.

➢ EDITOR’S NOTE: En Vogue et Veritas is the evolution of Critically Yours. Each piece will be free to read until September 30, 2025, when the series becomes exclusive to paid subscribers. Thank you for being here at the beginning. ☆

En Vogue et Veritas: A series exploring the emotional architecture of personal style through the classical lenses of ethos (character), pathos (emotion), and logos (intellect)—revealing how fashion shapes, reflects, and expresses our inner worlds.

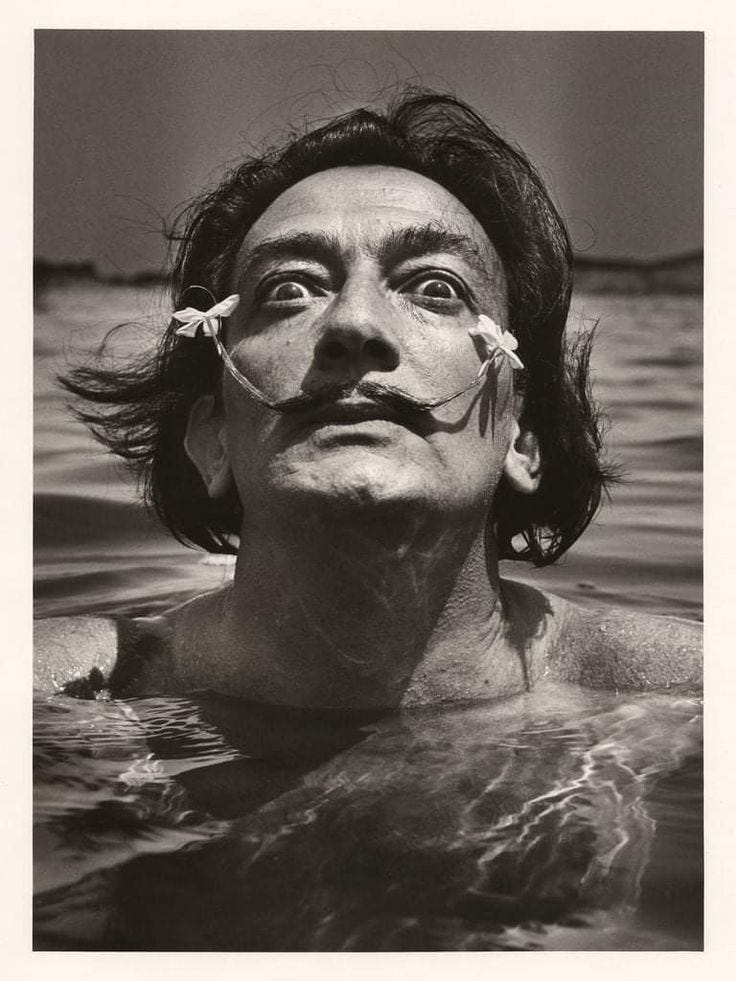

“Each morning when I wake up, I experience again a supreme pleasure—that of being Salvador Dalí.”

On May 11th of 1904 in Catalonia, Spain, the mythical wonder that was Salvador Dali was born.

But unlike most children, Dalí entered the world in shadow. Nine months before his birth, his elder brother—also named Salvador—had died of gastroenteritis at just 22 months old. Grief-stricken and unmoored, Dalí’s parents projected their sorrow onto their newborn son, naming him after the lost child and declaring him a reincarnation. From the moment he took his first breath, he was cast not as someone new, but as someone returned. He was loved not for who he was, but for who he might restore. Even his name was not his own.

From this early fracture, Dalí’s sense of self split: death and identity entwined, birthing a psyche both haunted and defiant. His sense of identity was not rooted in discovery but displacement. Who was he, if not his brother? Who could he become, if he was already spoken for?

Technically brilliant, emotionally volatile, and obsessed with time, memory, and the fear of vanishing, Dali’s fashion was never decoration—it was a way to prove that he, himself, was alive.

In this edition of En Vogue et Veritas, we unravel the enigma through the sacred trinity of Ethos, Pathos, and Logos—and discover how Dalí’s clothing reveals the beautiful ache of being alive.

Section I: Ethos, The Style of Character

Ethos /ˈē-ˌthäs/ (noun): From the Greek êthos, meaning character, custom, or moral nature. In rhetoric, it refers to the credibility and ethical appeal of the speaker. Ethos, in style, is how one’s core values are expressed through fabric and form.

“The only difference between me and a madman is that I am not mad.”

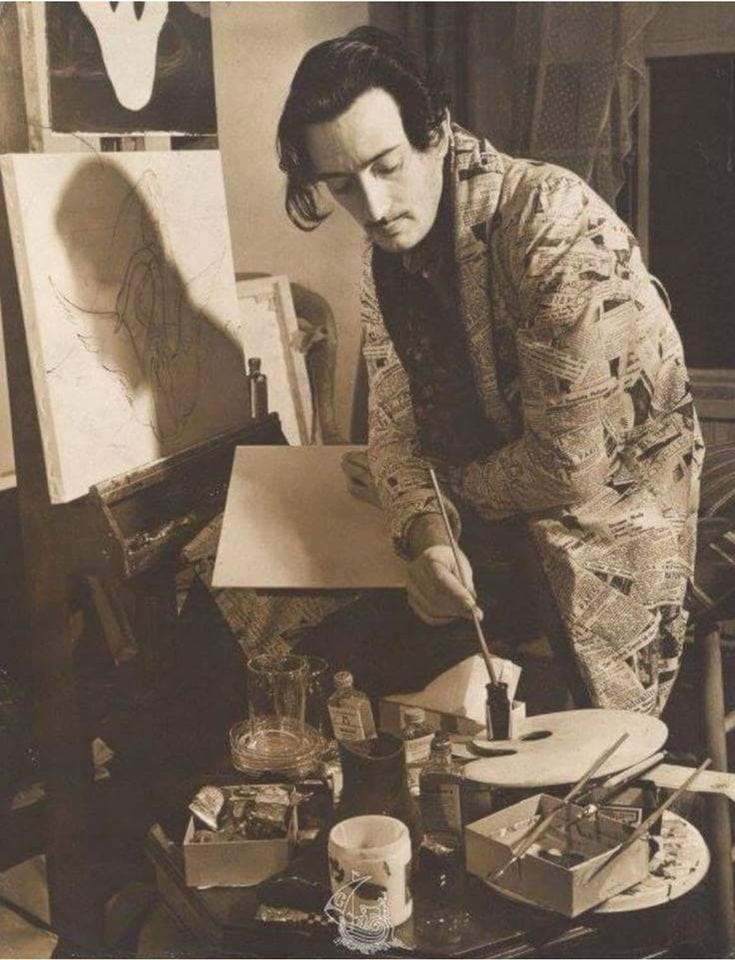

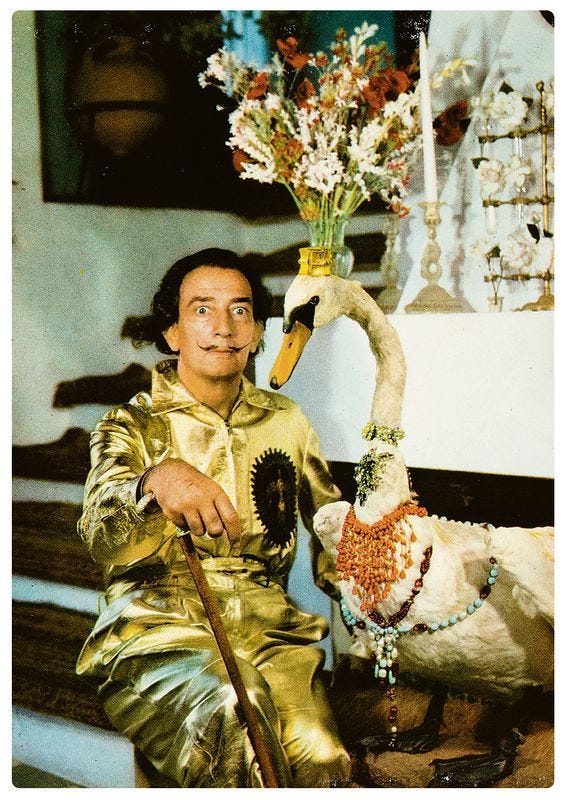

Trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid, Dalí quickly rejected tradition, aligning himself with the surrealists in Paris. Technically brilliant and instinctively gifted, his ethos embodied contradiction: a genius who played the fool. Reality, to him, was already absurd—so he lived in perpetual performance, not to entertain, but to escape. He had to be unforgettable, desperately trying to disown the shadow he inherited at birth.

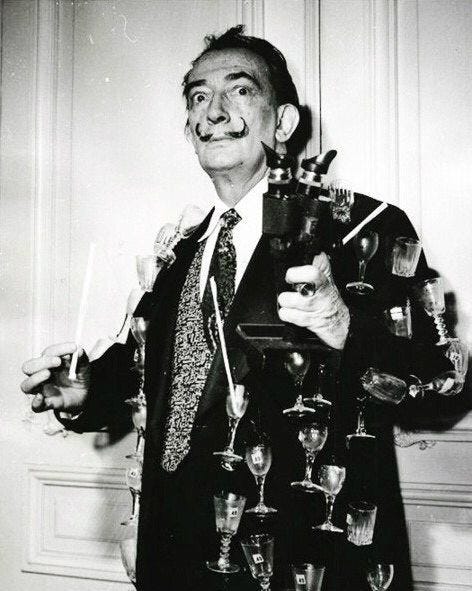

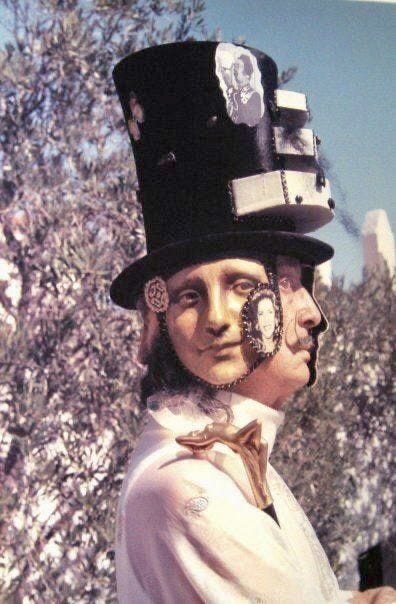

Dalí didn’t just want to be watched or admired—he needed to be seen. Through clothing, he cast himself as genius, jester, madman, and oracle all at once. Absurdity became his armor. He inverted the logic that seriousness must be subdued, making flamboyance his most credible claim to brilliance.

His painting The Great Masturbator (1929) captures the same ethos he wore on his body: erotic, grotesque, self-aware, and impossible to ignore. Dalí performed not for an audience, but for the muse of his own life. Every gesture, every outfit, was autobiography.

He crowned himself monarch of madness—repulsed by conformity, yet wielding the precision of a Renaissance master. He was elegance distorted, shock-value refined, forever toeing the line between spectacle and sincerity.

Section II: Pathos, The Style of Emotion

Pathos /ˈpā-ˌthäs/ (noun) From the Greek páthos, meaning suffering, experience, or emotion. Pathos is the emotional resonance of one’s feelings. In style, it is the visible ache or joy in how one dresses.

“I want to become a legend. I have no wish to be understood. I want to be adored.”

Dalí’s emotional life was euphoric, tortured, theatrical, lonely—the highs and lows of an endless opera. His style lived on the edge of fantasy and feeling—always elaborate, never accidental. Embroidery was emotion. Color, confession. Excess, catharsis.

In this grand, unending performance, misery played a starring role. When Dalí was sixteen, his mother died—a wound that never closed. Her absence became a ghost that followed him into every room. Later, Gala—his muse, his anchor, his undoing—tethered him to love and madness. Their bond was possessive, mythical, and posthumously haunting. After her death, he collapsed into silence, refusing to eat or speak for months, retreating into a world of solitude where even brilliance dimmed.

His heartache reverberates through his paintings, especially The Elephants (1948)—creatures of impossible fragility, their spindly legs straining beneath the weight of memory, grandeur tottering through a ghostly desert. In fashion, too, this pathos became protection. Every embellishment was a shield against oblivion: velvet suits, opulent cloaks, gem-encrusted canes—each an expression of longing draped in theatrical drag. He wore beauty as armor, absurdity as a way to laugh through grief.

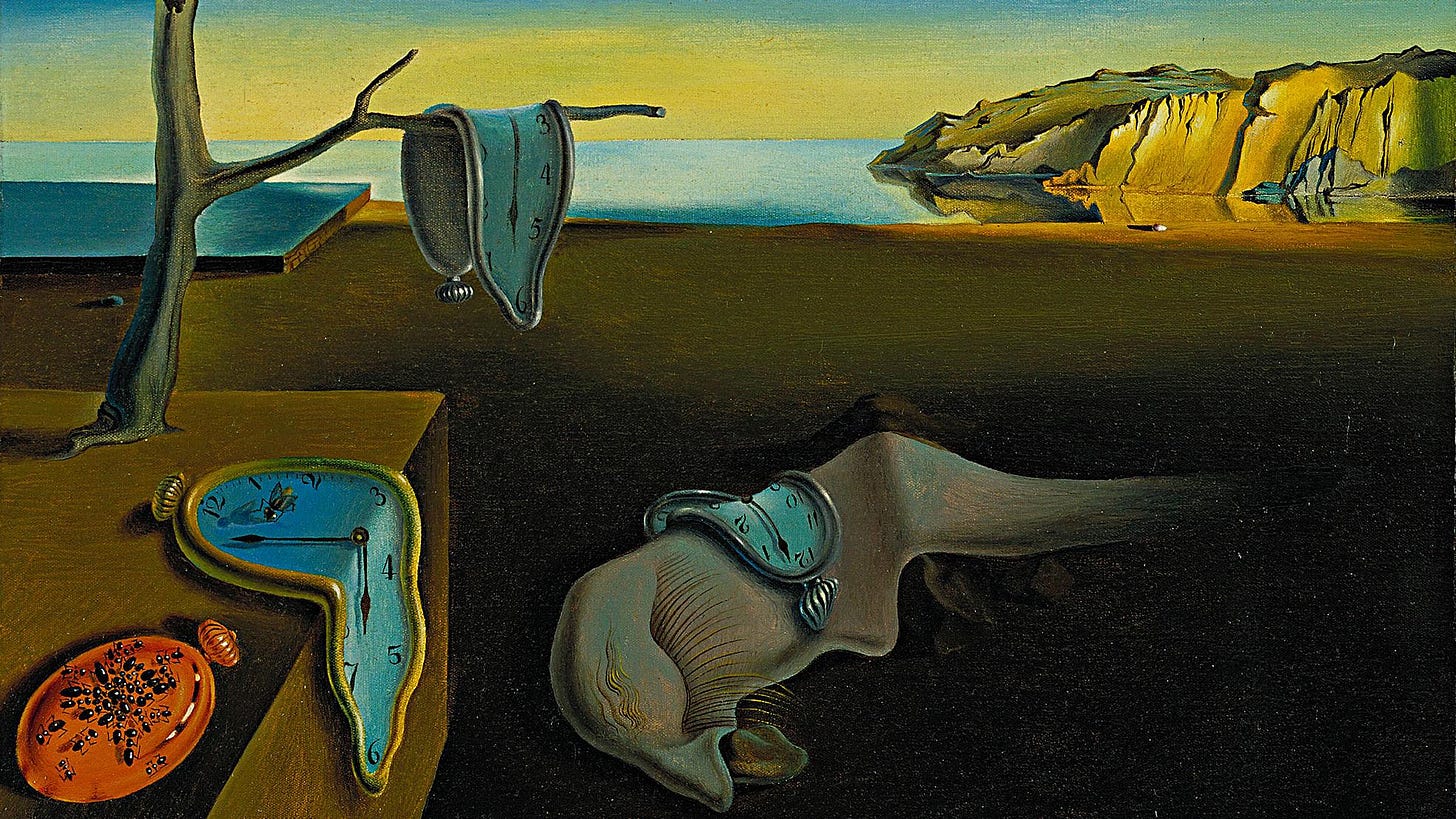

The Persistence of Memory (1931), his favorite and most famous work, crystallizes this sorrow. While often seen as a meditation on time, more deeply it’s about the surreal terror of time’s slow decay. The melting clocks, inspired by “camembert cheese melting in the sun,” transform softness into existential dread. Something rich and delicious turning to rot. He called it a “hand-painted dream photograph,” a portal into his inner world where the boundaries of logic melted under emotional heat. Time, to Dalí’s, was not rigid but mournful—bending, drooping, forever slipping away. Like his most theatrical ensembles, the painting embodies contradiction—stillness and distortion, beauty and decay.

Dalí felt everything in extremes. He feared death with a child’s horror. He loved Gala with cultish lust. He longed to be adored, to be remembered, but was disgusted when it came too easily. He teetered between fantasy and feeling, always elaborate, never accidental.

Section III: Logos — The Style of Thought

Logos /ˈlō-ˌgäs/ (noun) From the Greek lógos, meaning word, reason, or discourse. Logos is the logical structure behind an idea. In style, logos is expressed through personal, specific choices.

“It is not necessary for the public to know whether I am joking or whether I am serious, just as it is not necessary for me to know it myself.”

Dalí was an eternal student, layering his obsessions—geometry, classical painting, Catholic mysticism, Freudian theory, and nuclear physics—into both his art and his wardrobe. His clothing became a walking thesis. He used a cane not for balance, but to emphasize power. His suits were structured to resemble architectural detailing he adored, his obsession with symmetry was a visual ode to the Fibonacci sequence. Postwar, his fashion evolved to reflect his theory of nuclear mysticism—the idea that atoms, religion, and aesthetics were all expressions of divine order.

Dalí’s logos was paradox itself: chaos bound by structure, irrationality executed with intention.

His later works—like "Galatea of the Spheres" (1952)—attempted to reconcile atomic theory with spiritual transcendence, showing his belief that reason and magic were not separate, but spiraling partners. This desire to unify logic and the unknown shaped him mind and body: he was a man of obsessive detail. Each brooch, each print, each silhouette had purpose. He saw no distinction, no boundary, between art and science, intellect and intuition. Fashion, like painting, was a surface on which to explore his theory.

His clothes weren’t merely theatrical. They were equations, cosmologies, provocations. He didn’t dress to impress. He dressed to profess.

Closing Reflection

“Have no fear of perfection. You will never reach it.”

For a man terrified of death, Dalí achieved the impossible: he became immortal.

Haunted by memory, consumed by beauty, and desperate to escape the shadow he was born into, Dalí turned his life into a living myth. He made meaning out of the madness of life and great spectacle out of his sorrow. And in doing so, he accomplished what he craved most: to be remembered not merely for what he created, but for what he became—the greatest work of art.

Through ethos, pathos, and logos, Salvador Dalí existed in a way so vivid, so intentional, time itself melted in his presence— giving us, perhaps the most surreal truth of all: unlike a canvas, the self is never fixed. It can melt, mutate, and be endlessly reborn. Reinvention is possible, as many times as we would like it to be.

En Vogue et Veritas,

Alexandra Diana, The A List

Good Will, Worn Softly

The Sartorial Mind: A series exploring the emotional architecture of personal style through the lenses of ethos (character), pathos (emotion), and logos (intellect).

The Kennedy Identity: What JFK Learned from 007

“To be treated like royalty, you must act with confidence, but also restraint. A true king or queen never begs, never chases, never loses their composure.”

The Mystic, The Rebel, The Artist

"With freedom, books, flowers, and the moon, who could not be happy?”