➢ Personas explores a series of individuals I find most compelling by way of ethos, pathos, and logos, using style as a symbolic language for how we shape and disguise the self.

✧ Editors Note: This series will be free to read until September 30, 2025, when the series becomes exclusive to paid subscribers. Thank you for being here at the beginning. ✧

“I want to live always at the extreme of emotions, to live as if life were burning on my skin.” Anaïs Nin

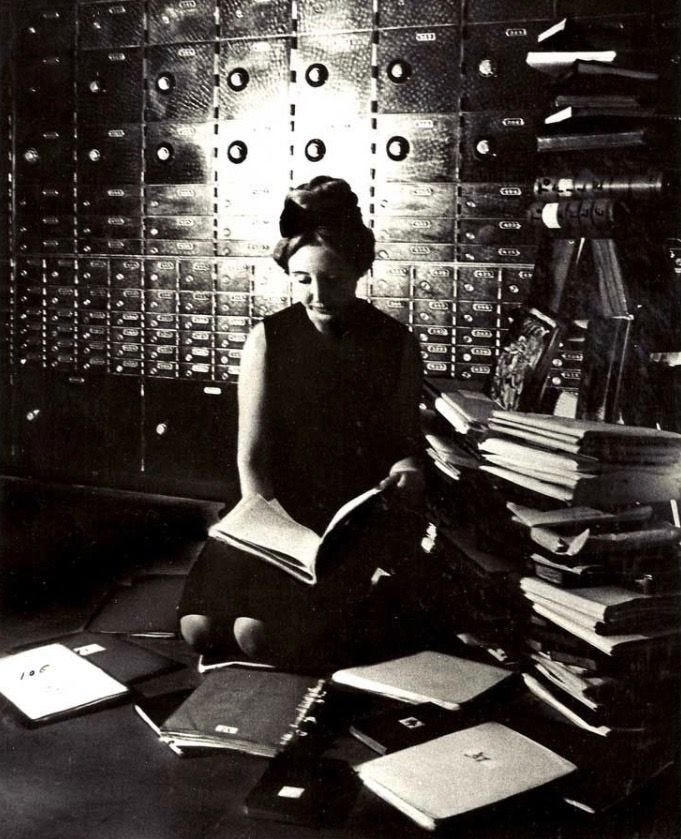

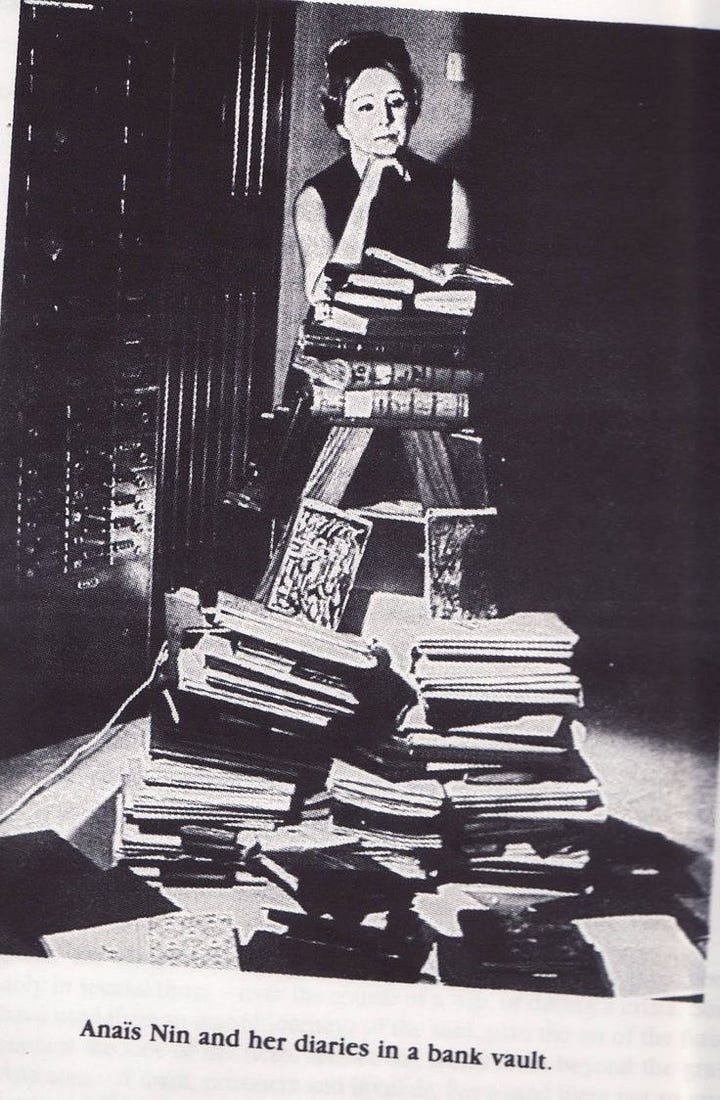

Anaïs Nin is one of the most spoken-about writers of the last century, and just as fascinating a subject as she intended herself to be. She wasn’t just a diarist; she was a character in her own myth, writing as both author and protagonist across more than 15,000 pages. Her life wasn’t documented, it was staged, edited, and re-performed in over 150 volumes of diaries.

When the unedited versions were finally released after her death, I can only imagine the chaos. It must have felt like watching a stage play flip into a documentary in real time. The shock that must’ve rippled through her orbit, former lovers, admirers, family members, must’ve been something close to theatrical violence.

She’s captivating because she’s so strange, so sensational. Profoundly self-aware yet incredibly deceptive, reading her work feels a little fracturing, going back and forth, confirming and denying what you did and didn’t read. I found myself doing this the the level of near compulsion. The things she admitted to and wrote about proved that while deeply flawed, her individuality couldn’t be questioned. She is a monument of self, perverse, strange, erotic and mutable, perceptible to any slight change, and capable of creating tidal waves.

Section I: Ethos, The Mask of Character

Ethos /ˈē-ˌthäs/: From the Greek êthos, meaning character, custom, or moral nature.

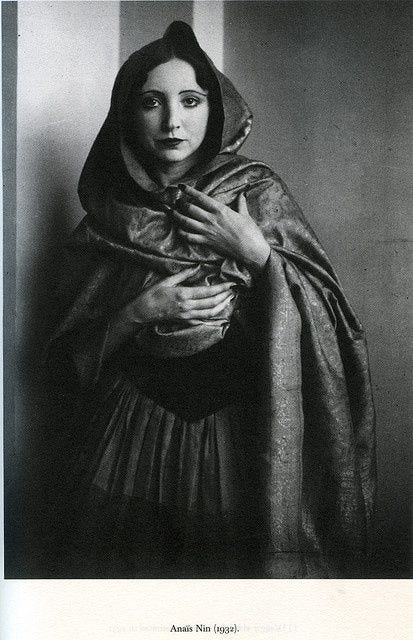

Anaïs Nin was many things: cosmopolitan, poetic, erotically fluid, spiritually attuned. Her cultivated persona was a mystic in silk gloves, a rare beauty, always mid-sentence, seemingly exisitng somewhere just out of reach. None of what she presented was accidental, as her ethos wasn’t a reflection of her character, but rather, was her character. Anaïs Nin deliberately authored herself, relentlessly, revising in realtime to suit her needs and emotional balance.

When she was eleven, she began writing in her diary as a letter to her absent father. This act of writing into the void set the stage for her emotional perception of her entire life; over the years, her diary became her co-conspirator: a place to shape truth rather than confess it.

During her lifetime, she published seven volumes of heavily edited diaries starting in 1966. These were curated to reflect a lyrical, sensual, spiritually evolving woman, the Anaïs the world was meant to admire. What the world didn’t know was that these diaries were heavily edited: she removed whole sections, rewrote history, removed vile details that were crucial parts of understanding who she was.

Secretly, she kept the unexpurgated versions hidden, sealed in boxes, entrusted to her literary executor, with explicit instructions to publish them only after her death. And when that day came, the carefully constructed world she had built ruptured under the weight of the grotesque and undeniable: her incestuous affair with her father, her two simultaneous marriages, the emotional unravelings she had once edited into submission.

She choreographed her own unmasking, she exposed herself with the level of drama Cleopatra would admire. For us, she left two Anaïses: the one crafted to be admired in life, and the one designed to haunt us in death.

What’s most compelling is how her writing feels like a mirror you’ve fallen into, but as you fall, you see the reflection is warped. She gives you everything, and yet you’re not quite sure if any of it is real. She may be the original manifestation of the manic pixie dream girl, however much darker, and far more elusive. She once said, “I made a world out of my obsessions.” And she did. Then she dressed it, lit it, edited it, and stepped inside.

Section II: Pathos, The Wound of Emotion

Pathos /ˈpā-ˌthäs/ (noun) From the Greek páthos, meaning suffering, experience, or emotion, the emotional resonance of one’s feelings.

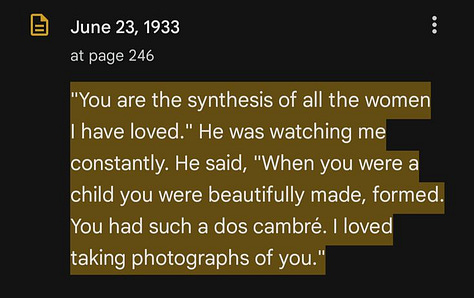

Joaquín Nin, her father, was known for seducing younger women, especially young students that often turned into admirers. He believed in the worship of genius, particularly his own, and saw his intellect as a moral exemption for his behaviors.

When they reunited in 1933, after twenty years apart, what happened was psychological warfare. Anaïs documented, explicitly and without apology, her sexual affair with her father. In her unexpurgated diary Incest she speaks to how she initiated, rationalized, and tried to position this act as psychic reparation, as a reclaiming of power. To be expressivley clear, this could never be accomplished by such perverse actions. This was a reenactment of abandonment, reframed as erotic triumph. It was deep trauma, encouraged by a man with no hint of morality, the twisted psychotic mind of a man who has no issue sexually exploiting his daughter.

After this affair, Anaïs spiraled into shame, obsession, dissociation. And yet, because she was a diarist, she never stopped trying to narrate it into meaning. She misunderstood the power she felt from writing as the power to rewrite her own psyche, however, this is not what power is. What happened to her was not powerful, it was fragmentation.

The mask she published, the sensual diarist, the liberated muse, left out other truths, such as her multiple marriages she achieved through forged marital documents. Her relationships with Henry Miller and his wife June were compulsive loops of obsession and repulsion. June, in particular, haunted her. She was erotically idealized but emotionally inaccessible, perhaps she mirrored the parts of Anaïs that Anaïs couldn’t hold, parts so abstract within herself, she couldn’t see them in another.

In her writing, she swings from the sadness of desperation to the confidence of someone with the most powerful aura in the room, leading me to think her emotions could flip on a dime, either by her own hand or someone else’s gaze. She seemed detached from her own behavior, as though her life were one long emotional experiment. I don’t think she cared much about the consequences of what she did to others, or herself; I think she cared about the story it left behind. She was obsessed with being misunderstood in the right way.

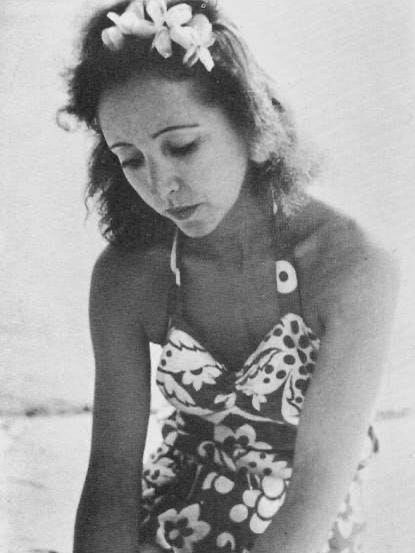

Even her clothing in this era reflects that split: not always polished, sometimes theatrical, often vulnerable. She wore bias-cut slips, sheer lace robes, soft knits off the shoulder, fabric that fell like a second skin, never stiff enough to hold its own shape. She was mutable, adaptable, ever-changing like water breaking out of its container.

Her diary became both containment strategy and compulsion, but it never quite worked. Her whole body of work reads like an ache for emotional coherence that never arrives.

Section III: Logos — The Mirror of Thought

Logos /ˈlō-ˌgäs/ (noun) From the Greek lógos, meaning word, reason, or discourse. The logical structure behind an idea.

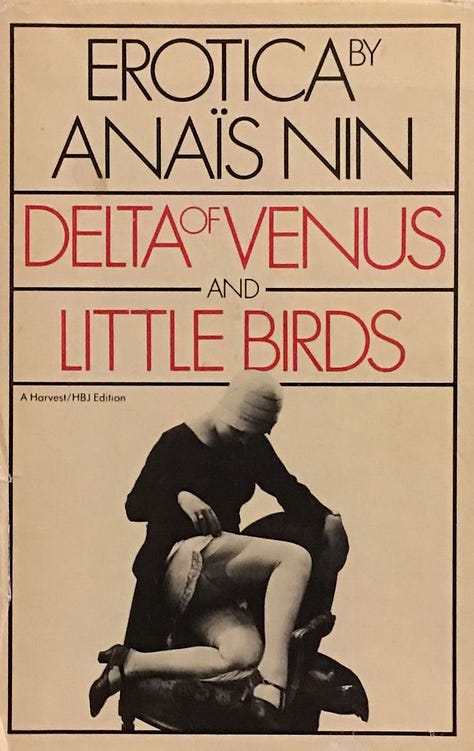

In The Novel of the Future, she made her stance clear: the inner life should be the organizing principle of fiction. Not facts. Not resolution. Certainly not morality. She believed in a “female form” of writing—fluid, recursive, porous. She wasn’t interested in what happened. She was interested in how it felt while happening.

In this way, Anaïs Nin’s contribution wasn’t just literary, it was philosophical. She redefined what narrative authority could look like, especially in autobiographical work. She rejected the flat linearity of traditional memoir and instead wrote in spirals, symbols, and self-reflections. What mattered most to her was interiority: emotion as structure, association as logic, poetry as truth.

She didn’t believe in binaries. Real versus imagined, ethical versus aesthetic, truth versus invention, all of these were nothing more than concepts to her. Her view of the world wasn’t fixed; it was an ever-changing improvisation, a grand opera. If her choices caused her to consider the morality of her actions, I believe instead of correcting the action, she questioned the need for morality.

To live without consequence is a deeply childish way to move through the world, but it’s a longing we all understand, if only a little. We forgive what we want to see in others, especially when it tells us something about ourselves. And Anaïs understood that. She knew how to mean something to people. She understood projection as intimacy. The more she withheld, the more we filled in. While she is a woman of many fragmentations, she is a genius in her ability to be raw and purely expressive, a true vessel for what it means to be human, deeply flawed and certainly impulsive.

Closing Reflection

In truth, I find it deeply relatable, to want to tell the version of the story you most long to hear about yourself. To control the chain of events, to choose which moments matter. To shape the narrative into something braver, stronger, more beautiful.

Life is one long reflection of self, easily warped. We can tell ourselves anything, and it’s shocking how effortlessly a thought can become reality if we rehearse it enough.

I think that’s the most enduring thing about Anaïs. For all her damage, for all her contradictions, she still refused to be bound by the rules of the physical world. She lived as if the imagination was the only plane that mattered. And maybe she was right. She proved that fantasy, sustained, sculpted, believed, can, in fact, become reality.

We don’t live in the world. We live in the story we’re telling about it.

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.”

With great personal aesthetic,

Alexandra Diana, The A List