Fashion History Series, Part IV

A series examining the historical influence of fashion on modern style

➢Previously covered: Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassical

The Romantic Era (1800-1850)

Romanticism was brought to life as a way to resist the strict, sharp lines of the Neoclassic Era and the rapid rise of industrialism. While smog formed and factories loomed, the romantics sought refuge in emotion, imagination, and nature. Dreaming backwards to medieval times, and forward into the sublime, the overwhelming feeling was a collective yearning to escape reality through beauty.

Where Neoclassicism spoke of restraint, Romanticism brimmed with emotion. Inspired further by literature and painting, fashion softened into billowing fabrics with natural silhouettes. Clothing was, for the first time, more than just an instrument to showcase class or citizenship. It became a way to express what one felt inwardly, out; mirroring the individuality and fragility of the human experience. Fashion and art were intertwined, together, at last.

Art of the Era

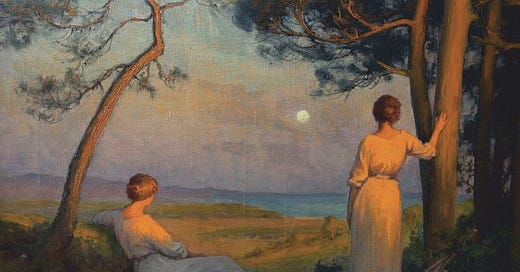

More than a parallel to fashion, Romantic art directly shaped the way people conceptualized beauty, feeling, and selfhood. The most significant shift was the focus on emotional intensity of the individual experience, rather than the theatrical grandeur of the Baroque, or the rational order of Neoclassicism. The ideal figure was no longer heroic or ornamental, they were sensitive, often solitary, and carried deep spiritual ponderance.

The following five works represent the core symbolic themes of the Romantic period: the sublime, the internal world, the fragility of life, and the longing for something just out of reach.

Caspar David Friedrich (German) – Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818)

This is widely considered the definitive image of the Romantic sublime—a man standing alone, enveloped in mist, facing the unknown. His posture echoes the Romantic silhouette: upright yet yielding, alone but symbolic.

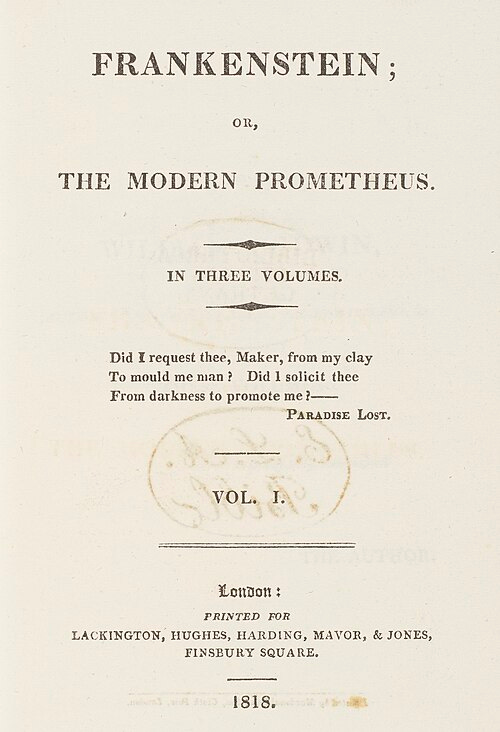

Mary Shelley (British) – Frankenstein (1818)

Written during a frozen summer in Geneva, Frankenstein has become the defining literary work of English Romanticism. Shelley was only eighteen when she created her masterpiece: a sapient creature stitched together from beauty and horror, only to be rejected by his maker. The novel explores themes of alienation, ambition, and the cost of creation, speaking directly to a generation in the midst of industrial progress, and the longing for human connection.

Romantic fashion mirrored Frankenstein’s themes: the fragile body, visualized longing, and constructed identity.

J.M.W. Turner (British) – The Fighting Temeraire (1838)

Turner’s painting shows a legendary British warship being towed by a steam-powered tugboat, on its final journey before being tossed and sold for scrap. Behind Temeraire, a sliver of Moon casts a beam across the river, a symbol for the new, industrial era. The “demise of heroic strength” is the main subject of the painting; it has been suggested that the ship stands for the artist, himself. Turner called the work his "darling".

Franz Schubert (Austrian) – Der Leiermann from Winterreise (1827)

Der Leiermann is the final song in Schubert’s Winterreise, written just a year before his death. The lyrics tell a story of a long man, playing in the snow, ignored by the world as he plays the same tune again and again. The melody is haunting and filled with an ache that captures Romanticism’s obsession with the solitary figure, and the dignification of suffering.

John Everett Millais (British) – Ophelia (1851–52)

Ophelia is one of the most iconic depictions of the Romantic Era. Shakespeare’s tragic heroine is shown drifting in a river, surrounded by flowers and moss, her hands open and eyes unfocused. The dress, seemingly hand-stitched and historically accurate, is nearly the focal point of the piece. Millais doesn’t depict death as violent, but as something soft, suspended, and beautiful. This is the most direct example of fashion, fabric, and emotion blending into one aesthetic whole.

The Philosophy of Fashion

The Mood of the Era

Romanticism’s aesthetic mood was one of yearning. As literature was consumed by tragic heroines, doomed love, and poetic melancholy, fashion responded with garments that blurred the boundary between self and story. These were not outfits designed for war or work, they were pieces for dreaming, writing, and fantasizing.

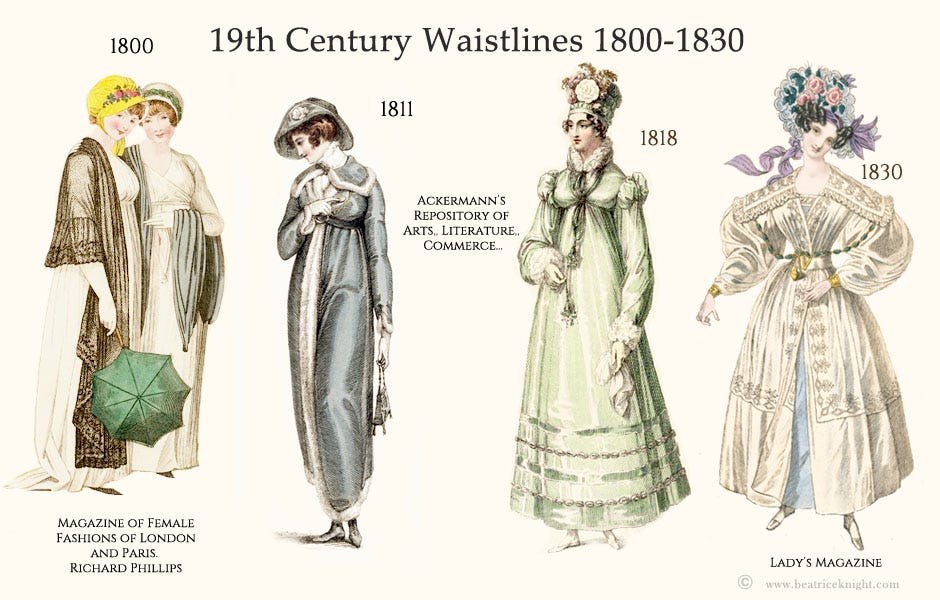

Key Garments & Silhouettes

The Met: Gigot Sleeve Example (1830)

Romantic Corsets

Unlike the rigid hourglass of later decades, Romantic-era corsets shaped the bust and upper torso with a gentler curve. For wealthier women, these corsets were made with fine cording, whalebone, and silk linings; for poorer women, quilted cotton and reed boning.

Victoria & Albert Museum: Early 19th-Century Corset

Reimagined Empire Lines

A holdover from Neoclassicism, the high waist remained, now with fuller skirts and softer fabrics that rippled with movement. Among the upper classes, muslins and silk taffetas flowed like watercolor; for working women, the same lines were achieved in heavier homespun or wool blends. For the first time, this silhouette was designed to elevate emotion, not status.

The Met: Empire-Line Gown, 1815

Bertha Collars and Pelerines

These wide, cape-like collars framed the neckline in ornate lace or embroidered cotton. Popular from the 1830s onward, they added theatrical softness to both daywear and formal dress.

Kyoto Costume Institute: Pelerine Collar Example

Men’s Frock Coats and Cravats

The Romantic man dressed like a fallen aristocrat or a published melancholic. Dark, layered, and severe, Romantic menswear showed a turn inward: looking more booding and introspective. For the bourgeois elite, these coats were tailored in fine wool and velvet; for the working man, simplified versions made from wool or brushed cotton.

The Met: Men’s Frock Coat, c. 1840

Symbolic Reversals

Romantic fashion was a deliberate reversal from the ideals of Enlightenment and Neoclassicism. Where previous styles praised symmetry, Romanticism celebrated imbalance. Where once clothing had marched in lockstep with political ideology, now it wandered through woods, ruins, and poems.

This wasn’t simply to outline your political standing, your wage or position in the social order. This was true fashion, as it was for the internal self.

I think that’s why it lingers, why it still feels like love. Romanticism didn’t dress to be understood, it dressed to feel. It wrapped longing in lace, stitched sorrow into seams. Its silhouettes didn’t assert, they lingered. In a time increasingly consumed by mechanized precision, Romantic dress whispered something rare: "Let me ache, and let me be beautiful because of it."

Modern Echoes

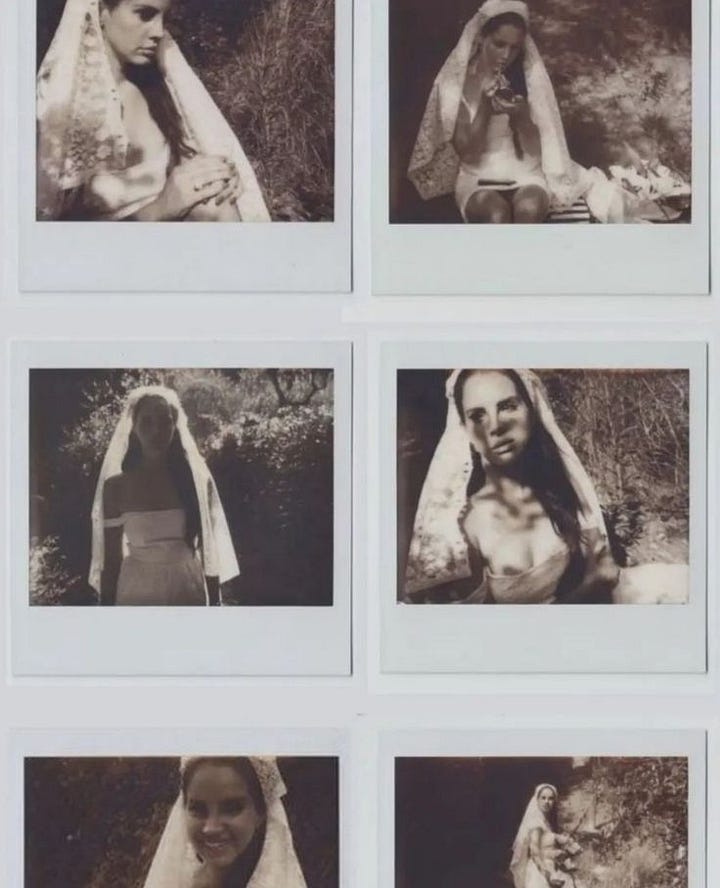

Lana Del Rey’s Visual World

Lana Del Rey is a master of atmosphere. Her visual language is deeply Romantic: Catholic iconography, Americana decay, and bridal gowns under cloudy skies. She evokes the tragic heroine in perpetual mourning, embodying the Romantic ideal that beauty is inseparable from sorrow. Her fashion makes feminine fragility the focal point, highlighted in a delicate, ethereal way; an aestheticized ache that Romanticism invented.

Alexander McQueen’s “Widows of Culloden” (Fall 2006)

In my opinion, the most Romantic runway show of the modern era. McQueen staged mourning in motion: ghosts of Scottish widows in tartan, lace, and gauze gliding down a fog-drenched catwalk. The show ends with a hologram of Kate Moss spinning in a glass box, the entire preformance an intoxicating display of feminine grace through sorrow. McQueen painted Romantic fashion in the perfect light, not decorative, sheerly devotional.

Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride (2005)

Ah, one of the best! The brilliance of this film distills the Romantic ethos into pure visual poetry. Emily, the Corpse Bride herself, is skeletal, dressed in a tattered wedding gown with trailing veil, delicate embroidery. Her design channels both the tragic heroine of Romantic literature and the late 19th-century fascination with death as aesthetic. There is a beautiful ruin, the Romantic obsession with death and love everlasting.

In Closing

Romanticism is the final breath we take on this earthly plane; the air of longing, the perfect moment of a hummingbird hovering in time. Its haunting, lovely, elegant and alone, it brings the humanity to despair, and the love intertwined in longing.

The silhouette of this era endures because we still crave what it gave us: the right to feel deeply, overwhelming, poetically and unapologically, and to wear that feeling like a second skin.

With great personal aesthetic,

Alexandra Diana, The A List

<3